Out of the Inkwell: A Celebration of Fleischer Studios

Bridging the gap between the technical innovations of the works produced by Walt Disney, often serving as testing grounds for techniques that he would utilize in his feature films, and the laugh-a-minute antics favored by the output at Warner Brothers, the animated shorts produced by Max and Dave Fleischer for the studio that bore their name from the early 1920s until 1942 continue to dazzle the eye and tickle the funny bone in equal measure. Alas, while a number of their creations have more than stood the test of time, the Fleischers and their contributions to the art of animation have sometimes been overlooked. Happily, an initiative to locate and produce 4K restorations of the Fleischer Studio’s output, spearheaded by Max’s granddaughter, Jane Fleischer Reid, has been on-going for the last couple of years. In its 2024 lineup, the Chicago Critics Film Festival is proud to present a program of the cream of the crop in their newly restored glory—an all-killer, no-filler lineup of animated classics that should go down as one of the major moviegoing events of the year.

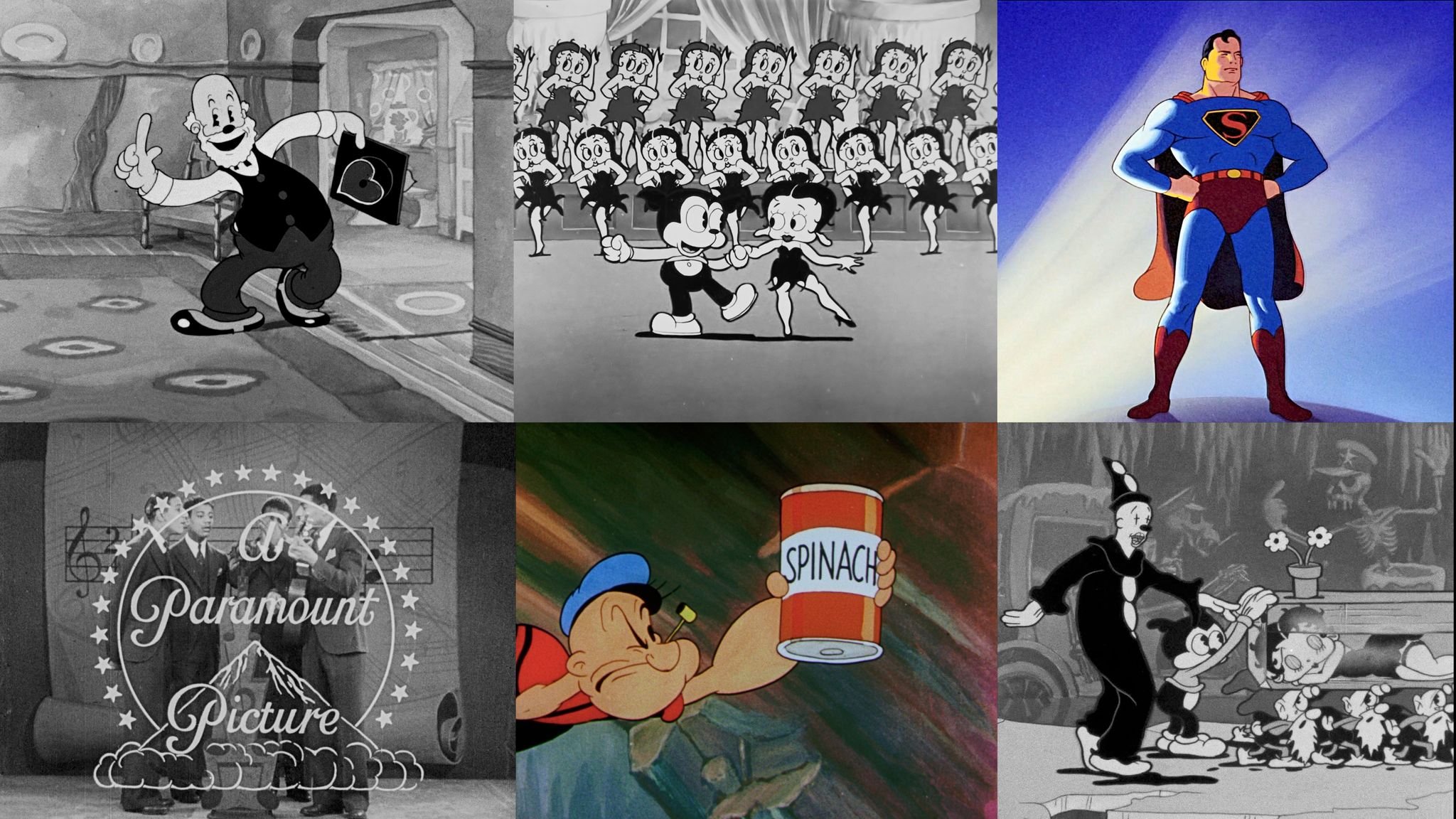

One early innovation the Fleischers utilized to impressive effect was the combination of live-action footage with animation, most notably via their Out of the Inkwell series (1918-1929), featuring the misadventures of Koko the Clown, often accompanied by his dog pal Fitz. One of the most startling uses of this technique came in the amusing, apocalyptic Koko’s Earth Control (1928), in which Koko and Fitz are brought to life by Max himself and happen upon a building that houses the various controls for Earth itself. Alas, despite his best efforts, Koko cannot prevent Fitz from pulling the lever that reads “Danger/Beware—If this handle is pulled, the world will come to an end,” a move that leads to wider-spread chaos than anything Michael Bay could devise.

As crazy as the imagery in that short becomes, it is a mere prelude to Bimbo’s Initiation (1931), a film so strange and surreal that clips from it pop up in both the Joe Dante segment of Twilight Zone—The Movie (1983) and the recent lo-fi chiller Skinamarink. In it, Bimbo, a regular Fleischer character that grew out of the aforementioned Fitz (and who was often seen as the love interest for the legendary Betty Boop), is walking down the street when he is forced into a manhole (by an assailant bearing a striking resemblance to another animated icon). This leads him to the underground club of a mysterious secret society, which is hell-bent on making him a member. Bimbo refuses, leading to a number of increasingly nightmarish ordeals, all presented in amusingly harrowing detail, before the short’s delightfully surprising and surprisingly delightful conclusion.

Speaking of Betty, a flirty flapper who remains the best-known and most iconic of the characters, she is well-represented here by one of her greatest shorts, Snow-White (1933), a work so bizarre and crammed with wild images that it almost makes Bimbo’s Initiation seem staid by comparison. You presumably know the story, but you have never seen it presented like this, from surreal imagery throughout to the astonishing number of gags crammed into every frame to Koko suddenly bursting into a performance of Cab Calloway’s “St. James Infirmary” that not only makes deft use of Calloway’s recording but also mirrors his unmistakable moves, rotoscoped by the Fleischer animators from footage of the man himself.

Another musical act that found themselves working with the Fleischers was the vocal quartet known as the Mills Brothers, who made three shorts for them that combined animation with live-action footage of them singing alongside a bouncing ball indicating the lyrics, to encourage audiences to sing along. Dinah (1933) was the second of these collaborations; while its animated section, featuring sailors loading and launching a cargo ship, may be somewhat subdued in comparison to other films, the short’s storm-tossed climax is suitably impressive, as is the Mills Brothers’ performance.

As for Betty, she brought something to studio animation that hadn’t been there before—genuine sex appeal. Within a couple of years, bluenoses would force the Fleischers to tone her character down, cutting back on the character’s sauciness, lengthening her skirts, and making her more of a pal than an object of desire. One of those pals was Grampy, an older inventor with a penchant for jury-rigging ordinary things into oddball creations. The character was introduced in Betty Boop and Grampy (1935), in which Grampy invites Betty to a party at his house that allows him to display such unique inventions as an umbrella retrofitted into a cake cutter and musical instruments that play themselves. This short may be little more than a collection of gags; but when they’re this inspired, who’s complaining?

In addition to their own creations, the Fleischers also licensed two of the most popular comic book characters of the time, Popeye and Superman, to create animated adventures for both. One of the most notable Popeye shorts is Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba’s Forty Thieves (1937), a two-reel, full-color extravaganza in which the sailor, accompanied by Olive Oyl and Wimpy, head to Arabia to battle the aforementioned 40 thieves, led by Abu Hassan (who bears an odd resemblance to the character’s longtime nemesis, Bluto), in an epic tale that combines nifty sight gags, a number of catchy tunes, and the Fleischers’ unique process of blending animation with miniature sets, to create an 3-D-like sensation as eye-popping today as it must have felt back in the day.

As for Superman, The Mechanical Monsters (1942) was the second of the 9 shorts featuring the Man of Steel that the Fleischers produced. While the story may not add up to much—a madman embarks on a crime wave utilizing giant robots under his control until you-know-who arrives—the depiction of the title creatures and the mayhem they wreak is certainly memorable. In later years, this particular short would be referenced in everything from Hayao Miyazaki’s Castle in the Sky (1986) to Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004) and would also secure its place in Superman history for featuring the first instance of Clark Kent utilizing a phone booth to make a quick costume change.

To be able to see these Fleischer Studios classics in any form is, of course, a joy. To see them newly restored and in a theater that might well have played them during their original release is a genuine cause for celebration. If you have somehow never seen these films or heard the Fleischer name before, this program will instantly convert you into a devoted fan. Certainly, more than Bimbo, experiencing Fleischer Studios’ finest is an initiation you’ll surely welcome.

Peter Sobczynski has been a programmer for the CCFF since its inception and is also a board member of the Chicago Film Critics Association. He is a contributor to such sites as RogerEbert.com and The Spool, as well as his own semi-dubious Substack, Auteurist Class. He can also be heard discussing new Blu-Ray releases on the Movie Madness podcast on the Now Playing Network with fellow critic Erik Childress.